This year's Oscar race has truly been the closest in ages for a reason: all superb films so closely yoked that it's hard to choose one over the other. This was the dilemma for me this year but we are witnessing auteurs really deep into their leaning to create painstaking art that may take a couple viewing to stick but once it sticks, it transports you into realms that you never imagined possible.

Here are ten such lovely realms...

1. A HERO (directed by Asghar Farhadi):

with his signature style of capturing everyday moments as silently as possible, Farhadi allows us to connect the dots for ourselves as we watch Rahim (Amir Jadidi) sink further into a situation beyond his control but one he should have been able to pump the breaks on at any moment. Jadidi wears this jaded yet tense look of frustration as he lurches from plot to plot, emboldened by others eager to cash in on a supposed good act by him for their own PR purposes. In the process, he not only loses his soul but it begins to suck in his family and the benefactors around him too deeply invested in an optimistic outcome to really examine the devil in the rather sketchy details.

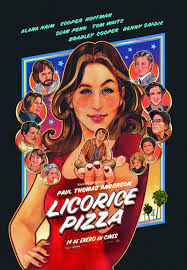

2. LICORICE PIZZA (directed by Paul Thomas Anderson):

A comedy, a drama, a romance, a memory, Licorice Pizza is the director’s warmest and fuzziest creation. But this isn’t a return to some missed or forgotten form – a half-careful look at any one of Anderson’s films, even the harder-edged likes of The Master and There Will Be Blood, reveals a man who has always been a giggly comedian, a sly observer of human foibles, a conjuror of worlds, a hopeless romantic. With its San Fernando Valley setting, its playful remixing of history and culture, its love of cosmic happenstance, its pursuit of all-deliberate-speed momentum, and its deeply flawed characters grasping onto one another with a desperate kind of manic glee, Licorice Pizza represents the uber-P.T.A. picture. If you have ever fallen in love with one of his films, then you will become instantly smitten here. And if you have ever felt hard done by one of his films, for whatever reason, then consider this a humble plea to at least sample a tiny little slice of his peculiarly flavoured pie. (Barry Hertz, THE GLOBE AND MAIL)

3. THE WORST PERSON IN THE WORLD (directed by Joachim Trier):

Trier’s film is divided up into little chapters, each with a clever or suggestive title. These almost-vignettes follow the rise and fall of Julie and Aksel’s romance and then beyond. There is a sustained encounter with another man—the goofier, more easygoing Eivind (Herbert Nordrum, winsome and sweet)—and then a dramatic turn that more explicitly, and persuasively, lays out the movie’s themes. Trier pulls a lot of stylistic tricks in the film, but they somehow never play like gimmicks, like adornments merely there to show off the talent of their creator. The film has a lilting, lively rhythm; the glimpses we see of months and years in Julie’s life ably provide a whole picture. (Richard Lawson, VANITY FAIR)

4. THE LOST DAUGHTER (directed by Maggie Gyllenhaal):

In every mother a sliver of ambivalence about motherhood; in every pretty doll’s mouth a worm. “How did it feel, to be away from your daughters?” asks Nina, expecting a reply full of angst and regret. The regret is there but the reply that comes – “It felt amazing,” says Leda – is the more honest because it is so unexpected. This is how Gyllenhaal has, with a blazing certainty that seems borderline miraculous in a first-time filmmaker, engineered “The Lost Daughter” to work, so that even though very little actually happens, the way that things don’t happen is somehow an ongoing, gripping surprise. The tension is born of an uncertainty, in any given situation, over how Leda, so unforgettably embodied by Colman, will behave. The suspense is that of an orange being peeled in a long strip that seems like it must break at any moment. And it will surely strike the rawest of nerves in anyone – mother or not – who staggers through the world with the demeanor of an ordinary decent person, when all the while feeling the thump inside of her strange heart beating where it lies. (Jessica, INDIEWIRE)

5. THE FRENCH DISPATCH (directed by Wes Anderson):

The anthology format fits Anderson like an Agnelle. Working with a giant ensemble cast of old and new collaborators, he dabbles in puckishly exaggerated art-world satire, pivots to an extended homage to the French New Wave, and finally indulges in one of his signature madcap chases (situated, as is often the case, in the closing stretch). The storytelling is as paramount–and often as dizzyingly entertaining—as the stories themselves. Building on the nesting-doll games of The Grand Budapest Hotel, Anderson cuts back and forth from the tales to their authors recounting them, on stage during a lecture or on a Dick Cavett-like talk show. He nestles frames within frames. (A.A. Dowd, AV CLUB)

6. DRIVE MY CAR (directed by Ryûsuke Hamaguchi):

the most rewarding aspects of Drive My Car stem from directorial decisions to elongate and extrapolate. It is in these drawn-out moments of quiet (and at times foreboding) conflict, the intensity of internal turmoil slowly seeps onto the screen. Whether manifesting as a lingering shot of delicate hands holding cigarettes outside of car windows or a bird’s eye view of traffic crawling along winding highways, there is always a stark revelation on the precipice. While these moments are often subdued or seemingly insignificant for propelling the narrative, the richness of their visual and emotional scope balance the relative sparseness of dialogue or character motivation, silently documenting dynamics playing out. (Natalia Keogan, PASTE)

7. RIDERS OF JUSTICE (directed by Anders Thomas Jensen):

when a seemingly innocent train of events lead to tragedy, it all ends up in the vicious hands of Markus (Mads Mikkelsen), a soldier who spares few words and even fewer moments of emotion. This black satire slyly looks at the orchestration of revenge and the casualties that come some unhinged and others barbaric beyond recognition.

8. TITANE (directed by Julia Ducournau):

Revising your preconceptions at frantic speed, you might decide that Titane is a Cronenberg-ish sci-fi body horror crossbred with a Tarantino-esque caper about a natural-born serial killer. But not even that gonzo definition will suffice. On the run, our scowling anti-heroine chops off her hair, breaks her own nose (I told you about the winces), and passes herself off as a boy who disappeared a decade earlier. The next twist is that the boy's tough-but-tender father, Vincent (Vincent Lindon), takes her at her word. He drives her back to the fire station under his command and introduces her to a sceptical team of hunky fire fighters. To maintain her new male identity, Alexia has to bind her oily breasts and her swelling stomach, but Vincent injects steroids into his bruised buttocks every night, so who's counting? The point is that Titane has mutated into a warm redemption story of gender fluidity, body modification, and plenty more besides. (Nicholas Barber, BBC)

9. THE POWER OF THE DOG (directed by Jane Campion):

At times, the storytelling is so nuanced that the film threatens to stall. As a viewer, you want the catharsis of a gunfight or a saloon bar brawl. Campion, though, deliberately avoids big dramatic set pieces. She is dealing with violence and sexual longing but in a very subtle and oblique way. All the characters’ feelings here are very deeply sublimated. The fascination of The Power of the Dog lies in its ambiguity and its depth of characterisation. Nothing is obvious here, not even the title. (Geoffrey McNab, THE INDEPENDENT)

10. LUCA (directed by Enrico Casarosa):

All that atmosphere serves the friendship that sits comfortably at Luca‘s core, a fantastic little tale of stepping out of the familiar and discovering yourself in new environments. That wouldn’t work without the central friendship between Luca and Alberto, which is beautiful and fragile in all the best ways. In many ways, the two need each other: Luca needs Alberto’s devil-may-care attitude to push himself to exit his comfort zone, and Alberto needs a friend to make him feel less alone. Their dynamic is beautifully reflective of the kind of formative friendships you have in your teen years — those gossamer summers with no responsibilities and endless possibility, with the perfect person by your side to experience it with. (Clint Worthington, CONSEQUENCE)